Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt is 25 years since two passenger trains collided at Ladbroke Grove, two miles west of London’s Paddington station.

The disaster was one of the worst rail crashes of the last century and resulted in 31 people dying and 417 being injured.

One of the trains had passed a signal set at danger.

It was a watershed moment for rail safety, and the consequences are still felt today.

‘Culture of complacency’

At 08:06 BST on 5 October 1999, a Thames Trains service to Bedwyn in Wiltshire collided with a Great Western high speed train from Cheltenham to London.

The combined speed on impact was 130mph (209km/h).

The leading carriage of the diesel multiple unit was largely destroyed. The fuel it was carrying ignited, leading to fires on both trains.

Most of those who died were on the Bedwyn train.

The Thames Trains driver, 31-year-old Michael Hodder, and 52-year-old Brian Cooper, driver of the Great Western service, were among the dead.

Mr Hodder, who came from Reading, passed a red signal, SN109, on an overhead gantry.

He was inexperienced, having qualified only two weeks before the crash.

The subsequent inquiry identified deficiencies in his training, including not being notified of recent incidents at the same signal.

Signal SN109 had been passed at danger eight times in six years.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe crash happened on a clear autumn morning, and the sun would have been low in the sky, behind Mr Hodder, meaning the sunlight would have reflected off the signal, reducing visibility.

Several years after the crash, Thames Trains was fined £2m after admitting breaches of health and safety legislation. Network Rail, the successor organisation to infrastructure owner Railtrack, was eventually fined £4m in 2007.

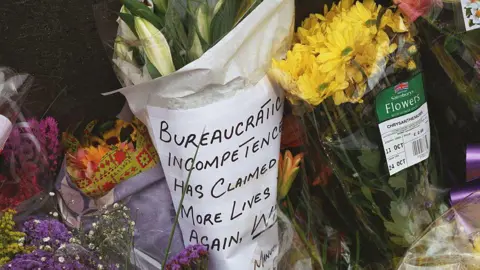

A small memorial garden overlooks the site, and vigils are held each year.

Alan Macro, from Theale in Berkshire, survived the crash.

He was physically unhurt, but says he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.

“The railway has become a lot safer since the crash,” he said.

“Mainly because of the Train Protection and Warning System that was introduced afterwards.

“But I thought that was an interim solution, and I am disappointed that more progress has not been made installing more comprehensive automatic system that stops trains from passing red signals.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAn inquiry led by Lord Cullen detailed issues with the signals, following ineffective management. The Cullen Report referred to “how so many apparently good people could produce so little action,” and heard of “a seemingly endemic culture of complacency and inaction”.

Only two weeks before the crash, it had been announced that the Train Protection and Warning System (TPWS) would be adopted across the network. It was a lower cost safety mechanism that could stop most trains within the overlap distance beyond a red signal.

This remains in widespread use. A pair of electronic loops in the track, looking like a grid or electric toaster, automatically cause a train to brake if it approaches a danger signal too fast.

“This was the biggest and most dramatic change,” said Martin Frobisher, Network Rail’s safety and engineering director.

“This interim technology has outperformed all expectations.

“It wasn’t the perfect technology. But the perfect technology would have taken a vast investment and decades to introduce, by re-signalling everything.”

Between 1900 and 1999, passengers died nearly every year in crashes caused by a Signal Passed At Danger (SPAD).

But in the quarter-century since Ladbroke Grove, there has not been a fatality caused by SPAD.

This is despite the number of SPADs remaining stubbornly close to 300 every year, with the Salisbury tunnel crash of 2021 the most serious recent example.

The crash led to the creation of three safety organisations with railway responsibility.

This separated the setting of standards, regulation and accident investigation.

“There has been a dramatic drop in risk over the period since then,” said Andrew Hall, chief inspector of rail accidents.

“Some of those gains have come by technology, some come from a better understanding of risk and some come from a structure that better looks at accidents and learns from them.

“There are now fewer issues at level crossings and ‘red-zone’ working on the track is now more or less eliminated at Network Rail.”

Mark Phillips, chief executive of the Rail Safety and Standards Board, said: “We are developing a future train protection strategy.

“Better understanding human factors is a big area of our work, including driver fatigue and how to maintain concentration.

“And we are looking at enhancing TPWS to give real-time information to drivers about the permitted speed. A modern car displays the speed limit wherever you are. It should not be difficult or expensive to have that capability on a train.”

Network Rail’s Martin Frobisher said: “Twenty-five years is a long time.”

He believes it is “important that we don’t lose the lessons of Ladbroke Grove”.

“This is about corporate memory, and the need for a new generation of railway engineers to be as focused on signals passed at danger as we have been,” he said.

“We’ve made great progress. But don’t be complacent. Don’t forget.”